What “Calories In, Calories Out” (CICO) Is

Simply, CICO says that gaining or losing weight is based on how many calories you consume (what you eat and drink) and how many calories you burn. If you burn more than you consume, you will lose weight; if you consume more than you burn, you will gain weight.

“Calories Out” encompasses:

- Resting Metabolic Rate

- Physical activities—exercise, walking, household activities, etc.

- Thermogenesis—food digestion, energy production, etc.

- Non-exercise activities like movement, standing, moving legs and arms, etc.

CICO is governed by the laws of thermodynamics: when energy (calories) is surplus and is being spent, the body stores it; when energy output is high and is being used up, the body uses stored fat.

But in reality, things are a little more complicated—it’s not as simple as “count calories and move more.” I’ll explain why below.

What the new research is teaching: Exciting twists and complexities of CICO

Research between 2020 and 2025 has shown that while CICO theory is true, it is influenced by a number of biological, behavioral, and environmental factors. Here are some key ones:

1. How we “adapt” (Metabolic Adaptation / Adaptive Thermogenesis)

When you lose weight on a diet, the body doesn’t merely lose weight—its energy expenditure (resting + activity) also drops, just not as much as you’d think.

- Obese individuals lost approximately 13% of their body weight, and their resting metabolic rate decreased approximately 90 calories/day below estimated RMR after 8–9 weeks. That is, their bodies started using fewer calories.

- This “adaptation” is most dramatic when you are in a chronic calorie deficit (when you’re losing weight). But after you stabilize at your new weight, the deficit drops—but does not zero out.

- And this adjustment is tied to hormonal adjustment—hormones such as leptin, which signal hunger and the body’s energy status, fall; hunger rises.

So the body is essentially taking a “defense” approach when it’s losing weight.

2. Energy expenditure varies with varying approaches to weight loss.

The weight loss method makes a difference:

- For instance, individuals who undergo bariatric surgery (weight loss surgery) experience a different impact on total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) compared to individuals who simply go on a low-calorie diet. Those undergoing surgery lose weight faster and have a greater reduction in energy expenditure at first, but that shifts with time.

- Occasionally, when individuals cut calories, they decrease their day-to-day non-exercise activity—that is, they stand less, walk less, and move less. This also decreases calorie burn, frequently without their knowledge.

3. Hunger, hormones, and feedback signals

In addition to decreased calorie burn, the body does things that boost hunger and food cravings:

- In a study, when individuals returned to baseline after eight weeks of a low-calorie diet, they felt hungrier, and their hunger hormone, ghrelin, went up. This correlated with how much their RMR decreased.

- Leptin, the hormone that says to the body, “enough is enough,” drops when fat loss happens. Reducing leptin means more hunger and less food satisfaction. That is why most people struggle to keep weight off after they have lost weight.

4. Everyone’s experience is different.

Even two individuals eating the same diet and deficit can experience things very differently:

- The RMR of some individuals falls more, some less; some become hungrier, some less. The impact of losing or gaining lean body mass is varied.

- Age, sex, genes, prior weight, proportion of muscle in the body, etc. have a very significant impact. Habits, routine, food, sleep, stress, etc. also contribute.

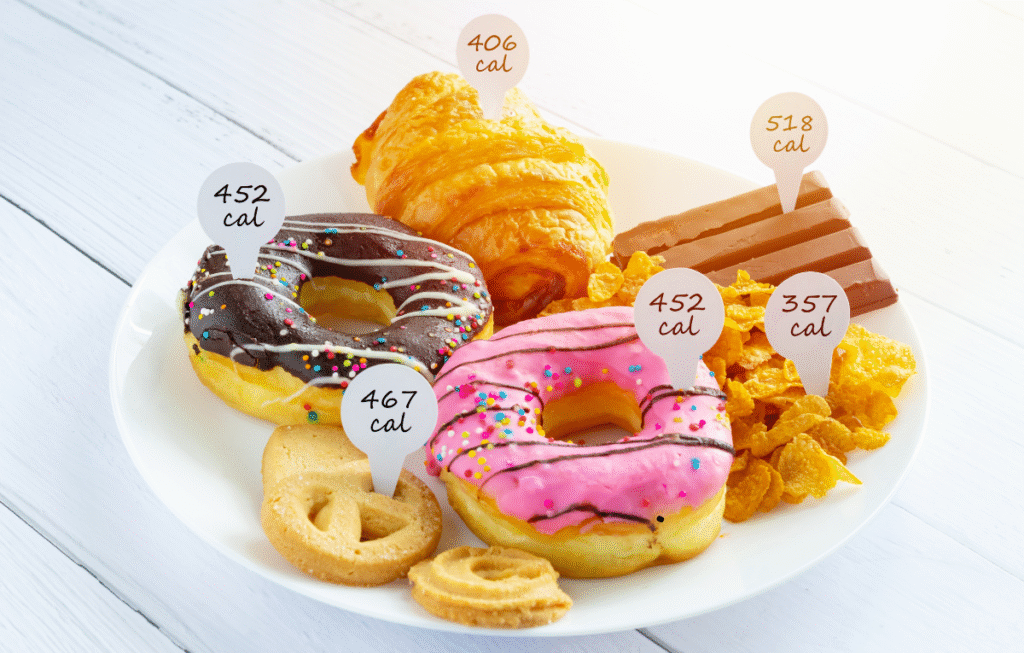

5. Calorie “quality” and the impact of variety of foods

It’s not so much the quantity of calories as it is the source of the calories:

- Entire and less processed foods: vegetables, fruits, and whole grains are full of fiber; these types of food require more time to digest, hunger is felt later, and some of the calories are “used up” from digestion.

- The form of food—solid versus liquid, how processed, how stimulating the flavor is—are all significant. For instance, consuming milk with honey or sugar might not fill you up as rapidly as solid foods.

- Protein has a greater thermic effect; it requires more energy to break down food. The shape of the food, chewing and digestion, the condition of the intestines, etc. also influence the “in” and “out” of calories.

The “New “CICO”—How We Should Understand It Now

With all these new revelations, CICO is no longer “eat fewer calories and move more”; we need to implement it more strategically:

- CICO remains the fundamental reality: lose weight. To lose weight, a calorie deficit is required. But choosing to reduce 500 calories a day won’t have the same effect on everyone.

- The body changes: When you lose weight, the body adapts—energy expenditure decreases, hunger increases—so you need to change tactics occasionally.

- Consistency beats cutting too much: Individuals who try more extreme diets can lose weight quicker at first, but hunger and fatigue will make them not last and make them relapse.

- Small, frequent changes tend to be more effective than dramatic changes since the body doesn’t need to be “shocked” by the change.

- Focus on food quality: Add more protein and fiber and eliminate highly processed and tastier but calorie-dense foods.

What recent studies show: examples

Some new research has established things such as

- Within obese individuals, individuals who had a larger “metabolic adaptation” (a larger than predicted reduction in RMR) failed to lose the anticipated amount of weight and fat on a calorie-restricted diet.

- In a second study that compared levels of hunger hormones and hunger, those who reduced RMR more experienced a rise in hunger hormones such as ghrelin and increased food desirability.

- Research comparing surgery finds that total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) drops remarkably after surgery, but patterns of eating and activity play a role in how stable the new weight will be.

New Strategies for Weight Control: What Works Best

The following are the things that new science indicates can result in better outcomes:

- Have a sensible calorie deficit, not so much because you can handle more in the long term but to cut down hunger, lack of energy, and tiredness.

- Take sufficient protein and keep muscle tissue intact. Muscle loss causes reduced resting calorie burn, which might slow down weight loss.

- Be aware of the potential for metabolic adaptation and modify the plan every so often accordingly—e.g., relaxing, “refeeding” (consuming a little more now and then), or keeping calories constant for several days to prevent the body from entering “crisis.”

- Keep up both exercise and regular movement—not only gym work, but also household chores, walking, taking the stairs, etc. are essential because those “non-exercise physical activities” tend to generate a bigger contribution to calorie burn.

- Pay attention to food quality: more fiber and protein and whole grains and fewer processed foods; balance with less sugary or fatty foods.

- Listen to hunger and eating habits; do not just focus on calorie counting. Better food choices when hunger is great and satiety is poor.

- Have a long-term view—weight loss is only the starting point; keeping it off is harder. Steady state, incremental change, flexible behavior, and daily habits are getting better.

Questions that are still unanswered

Some questions remain unanswered:

- It is unclear how much metabolic adaptation will take place in an individual and how we can have foreknowledge of it.

- It is still being studied how gut microbiome, fetal nutrition, and early life habits influence “calories in” or “out.”

- Fewer data are available on the impact of a specific diet on the body and health of an individual who has been following it for many years.

- Long-term weight loss maintenance strategies—behavior, cognition, and social and environmental support—need more research.

Conclusion

- “Calories in vs calories out” remains the simple rule for weight management—consume fewer calories, burn more calories, and you will be thinner. But minute changes, food, lifestyle, body reaction, and what creates equilibrium also matter.

- Those who are able to maintain consistency, consume adequate protein, know hunger control techniques, and incorporate non-exercise activity have positive outcomes.

- We’re all individuals; your age, muscle mass, genetics, and lifestyle all influence how much effort you’ll require.

FAQs

What does “Calories In, Calories Out” (CICO) refer to?

CICO refers to the fact that weight fluctuations depend on calories inputted versus calories expended. You lose weight if you intake fewer calories than you expend—if more, then you gain weight.

Is CICO accurate for everyone?

Yes, but it is not that straightforward. Numerous variables—such as metabolism, hormones, and dietary quality—influence how calories are utilized, making CICO extremely individual in reality.

What is metabolic adaptation during weight loss?

Metabolic adaptation refers to your body expending fewer calories than anticipated when losing weight. It’s a natural response to save energy and ensure weight stability.

SamhithaHealth & Wellness Content Writer

a Health & Wellness Content Writer with over 6 years of experience creating research-based health articles. She specializes in nutrition, weight management, diabetes care, skin health, and healthy lifestyle practices. Here content is carefully written using trusted medical and scientific sources to ensure accuracy and clarity for readers.